Goodbye, NullReferenceException: Option and LINQ

20 Mar 2023 #tutorial #csharpIn the previous post of this series, we covered three C# operators to simplify null checks and C# 8.0 Nullable References to signal when things can be null.

In this post, let’s learn a more “functional” approach to removing null and how to use it to avoid null when working with LINQ XOrDefault methods.

1. Use Option: A More Functional Approach to Nulls

Functional languages like F# or Haskell use a different approach for null and optional values. Instead of null, they use an Option or Maybe type.

With the Option type, we have a “box” that might have a value or not. It’s the same concept of nullable ints, for example. I bet you have already used them. Let’s see an example,

int? maybeAnInt = null;

var hasValue = maybeAnInt.HasValue;

// false

var dangerousInt = maybeAnInt.Value;

// ^^^^^

// Nullable object must have a value.

var safeInt = maybeAnInt.GetValueOrDefault();

// 0

With nullable ints, we have variable that either holds an interger or null. They have the HasValue and Value properties, and the GetValueOrDefault() method to access their inner value.

We can extend the concept of a box with possibly a value to reference types with the Option type. We can wrap our reference types like Option<int> or Option<Movie>.

The Option Type

The Option type has two subtypes: Some and None. Some represents a box with a value inside it, and None, an empty box.

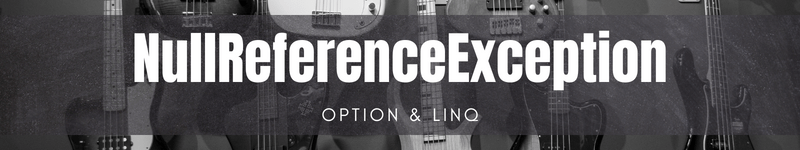

The Option has two basic methods:

- One method to put something into a box. Often we call it

Unit. For this, we can use the constructor ofSomeandNone. - One method to open the box, transform its value and return a new one with the result. Let’s call this method

Map.

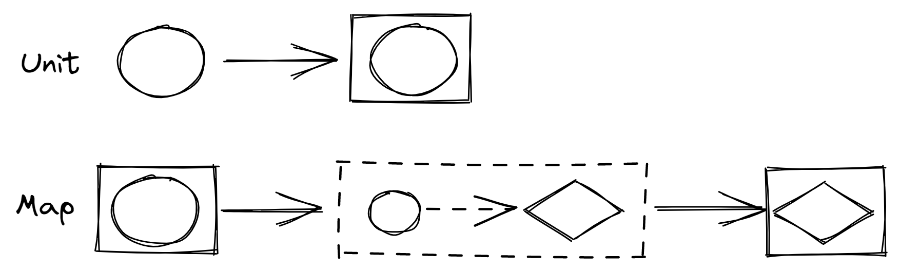

Let’s use the Optional library, a robust option type for C#, to see how to use the Some, None, and Map(),

using Optional;

Option<int> someInt = Option.Some(42);

Option<int> none = Option.None<int>();

var doubleOfSomeInt = someInt.Map(value => value * 2)

.ValueOr(-1);

// 84

var doubleOfNone = none.Map(value => value * 2)

.ValueOr(-1);

// -1

We created two optional ints: someInt and none. Then, we used Map() to double their values. Then, to retrieve the value of each optional, we used ValueOr() with a default value.

For someInt, Map() returned another optional with the double of 42 and ValueOr() returned the same result. And for none, Map() returned None and ValueOr() returned -1.

How to Flatten Nested Options

Now, let’s rewrite the HttpContext example from previous posts,

public class HttpContext

{

public static Option<HttpContext> Current;

// ^^^^^

public HttpContext()

{

}

public Option<Request> Request { get; set; }

// ^^^^^

}

public record Request(Option<string> ApplicationPath);

// ^^^^^

Notice that instead of appending ? to type declarations like what we did with in the past post when we covered C# 8.0 Nullable References, we wrapped them around Option.

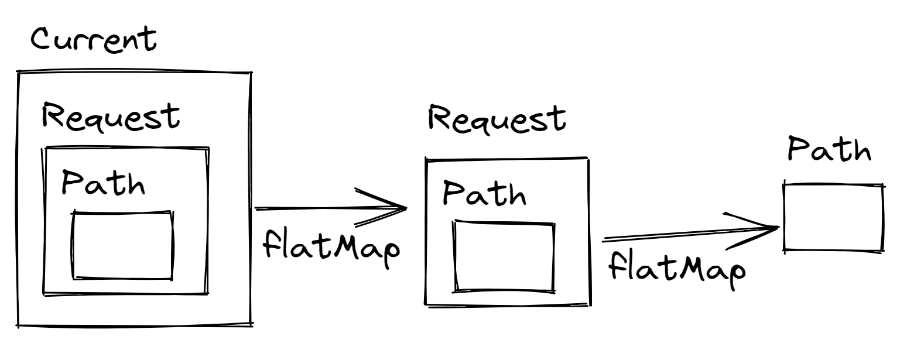

This time, Current is a box with Request as another box inside. And Request has the ApplicationPath as another box.

Now, let’s retrieve the ApplicationPath,

var path = HttpContext.Current

.FlatMap(current => current.Request)

// ^^^^^

.FlatMap(request => request.ApplicationPath)

// ^^^^^

.ValueOr("/some-default-path-here");

// ^^^^

// Or

//.Match((path) => path , () => "/some-default-path-here");

// This isn't the real HttpContext class...

// We're writing some dummy declarations to prove a point

public class HttpContext

{

public static Option<HttpContext> Current;

public HttpContext()

{

}

public Option<Request> Request { get; set; }

}

public record Request(Option<string> ApplicationPath);

To get the ApplicationPath value, we had to open all boxes that contain it. For that, we used the FlatMap() method. It grabs the value in the box, transforms it, and returns another box. With FlatMap(), we can flatten two nested boxes.

Notice we didn’t do any transformation with FlatMap(). We only retrieved the inner value of Option, which was already another Option.

This is how we read ApplicationPath:

- With

FlatMap(), we opened theCurrentbox and grabbed theRequestbox in it. - Then, we used

FlatMap()again to openRequestand grab theApplicationPath. - Finally, with

ValueOr(), we took out the value insideApplicationPathif it had any. Otherwise, if theApplicationPathwas empty, it returned a default value of our choice.

“This is the way!” Sorry, this is the “functional” way! We can think of nullable ints like ints being wrapped around a Nullable box with more compact syntax and some helper methods.

2. Option and LINQ XOrDefault methods

Another source of NullReferenceException is when we don’t check the result of the FirstOrDefault, LastOrDefault, and SingleOrDefault methods.

These methods return null when the source collection has reference types, and there are no matching elements. In fact, this is one of the most common mistakes when working with LINQ.

There are some alternatives to prevent the NullReferenceException when working with XOrDefault methods.

.NET 6.0 released some new LINQ methods and overloads. With .NET 6.0, we can use a second parameter with the XOrDefault methods to pass a default value of our choice. Also, we can use the DefaultIfEmpty method instead of filtering collections with FirstOrDefault.

Use Optional’s XOrNone

But, let’s combine the XOrDefault methods with the Option type. We can make the XOrDefault methods return an Option<T> instead of null.

The Optional library has FirstOrNone(), LastOrNone() and SingleOrNone() instead of the usual XOrDefault methods.

This time, let’s use FirstOrNone() instead of FirstOrDefault(),

using Optional.Collections;

// ^^^^^

var movies = new List<Movie>

{

new Movie("Shrek", 2001, 3.95f),

new Movie("Inside Out", 2015, 4.1f),

new Movie("Ratatouille", 2007, 4f),

new Movie("Toy Story", 1995, 4.1f),

new Movie("Cloudy with a Chance of Meatballs", 2009, 3.75f)

};

var theBestOfAll = new Movie("My Neighbor Totoro", 1988, 5);

// With .NET FirstOrDefault()

var theBest = movies.FirstOrDefault(

movie => movie.Rating == 5.0,

theBestOfAll);

// ^^^^^

// With Optional's FirstOrNone()

var theBestAgain = movies.FirstOrNone(movie => movie.Rating == 5.0)

// ^^^^^

.ValueOr(theBestOfAll);

// ^^^^^

Console.WriteLine(theBestAgain.Name);

record Movie(string Name, int ReleaseYear, float Rating);

By using the XOrNone methods, we’re forced to check if they return something before trying to use their result.

Voilà! That’s the functional way of doing null, with the Option or Maybe type. Here we used the Optional library, but there’s also another library I like: Optuple. It uses the tuple (bool HasValue, T Value) to represent the Some and None subtypes.

Even though we used a library to bring the Option type, we can implement our own Option type and its methods. It’s not that difficult. We need an abstract class with two child classes and a couple of extension methods to make it work.

Don’t miss the other posts in this series, what the NullReferenceException is and when it’s thrown, nullable operators and references, and separate optional state into separate objects.

Happy coding!