A beginner's Guide to Git. A guide to time travel

29 May 2020 #tutorial #gitDo you store your files on folders named after the date of your changes? I did it back in school with my class projects. There’s a better way! Let’s use Git and GitHub to version control our projects.

$ ls

Project-2020-04-01/

Project-Final/

Project-Final-Final/

Project-ThisIsNOTTheFinal/

Project-ThisIsTheTrueFinal/

1. What is a Version Control System?

First, what is a version control system? A version control system, VCS, is a piece of code that keeps track of changes of a file or set of files.

A version control system, among other things, allows us to:

- Revert a file or the entire project to a previous state

- Follow all changes of a file through its lifetime

- See who has modified a file

To better understand this concept, let’s use an analogy.

A version control system is like a time machine. With it, we can go backward in time, create timelines and merge two separate timelines. We don’t travel to historical events in time, but to checkpoints in our project.

2. Centralized vs Distributed

There is a distinction between version control systems that make them different. Centralized vs distributed.

A centralized VCS requires a server to perform any operation on your project. We need to connect to a server to download all our files to start to work. If this server goes down, we can’t work. Bye, bye, productivity! Team Foundation Server (TFS) from Microsoft is a centralized VCS.

But, a distributed VCS doesn’t need a centralized server in the same sense. Each user has a complete copy of the entire project. Most operations are performed against this local copy. We can work offline. A two-hour flight without internet, no problem. For example, Git is a distributed VCS.

If you’re coming from TFS, I’ve written a Git Guide for TFS Users.

3. What’s Git anyways?

Up to this point, Git doesn’t need any further introduction. From its official page, “Git is a free and open-source distributed version control system designed to handle everything from small to very large projects with speed and efficiency.”

How to Install and Setup Git

We can install Git from its official page. There we can find instructions to install Git using package managers for all major OS’s.

Before starting to work, we need some one-time setups. We need to configure a name and an email. This name and email will appear in the file history of any file we create or modify.

Let’s go to the command line. From the next two commands, replace “John Doe” and “johndoe@example.com” with your own name and email.

$ git config --global user.name "John Doe"

$ git config --global user.email johndoe@example.com

We can change this name and email between projects. If we want to use different names and emails for work and personal projects, we’re covered. We can manage different accounts between folders.

How to Create a Git repository

There are two ways to start working with Git. From scratch or from an existing project.

If we are starting from scratch, inside the folder we want to version control, let’s use init. Like this,

$ git init

After running git init, Git creates a hidden folder called .git inside our project folder. Git keeps everything under the hood on this folder.

If we have an existing project, we need to use clone, instead.

# Replace <url> with the actual url of the project

# For example, https://github.com/canro91/Parsinator

$ git clone <url>

Did you notice it? The command name is clone. Since we are getting a copy of everything a server has about a project.

How to Add new files

Let’s start working! Let’s create new files or change existing ones in our project. Next, we want Git to keep track of these files. We need three commands: status, add and commit.

First, status shows the pending changes in our files. add includes some files in the staging area. And, commit creates an event in the history of our project.

# git status will show pending changes in files

$ git status

# Create a README file using your favorite text editor.

# Add some content

# See what has changed now

$ git status

$ git add README

$ git commit -m 'Add README file'

After using the commit command, Git knows about a file called README. We have a commit (a checkpoint) in our project we can go back to. Git has stored our changes. This commit has a unique code (a SHA-1) and an author.

We can use log to see all commits created so far.

# You will see your previous commit here

$ git log

What’s the Staging area?

The staging area or index is a concept that makes Git different.

The staging area is an intermediate area to review files before committing them.

It’s like making our files wait in a line before keeping track of them. This allows us to commit only a group of files or portions of a single file.

If you’re coming from TFS, notice you need two steps to store your changes. These are: add to include files into the staging area and commit to create a checkpoint from them. With TFS, you only “check-in” your files.

How to Ignore Files

Sometimes we don’t need to version control certain files or folders. For example, log files, third-party libraries, files, and folders generated by compilation or by our IDE.

If we’re starting from scratch, we need to do this only once. But if we’re starting from an existing project, chances are somebody already did it.

We need to create a .gitignore file with the patterns of files and folders we want to ignore. We can use this file globally or per project.

There is a collection of gitignore templates on GitHub per language and IDE’s.

For example, to ignore the node_modules folder, the .gitignore file will contain

node_modules/

Git won’t notice any files from the patterns included in the .gitignore file. Run git status to notice it.

How to write Good Commit Messages

A good commit message should tell why the change is needed, what problem it fixes and any side effect it might have.

Please, please don’t use “uploading changes” or anything like that on your commit messages.

Depending on our workplace or project, we have to follow a naming convention for our commit messages. For example, we have to include the type of change (feature, test, bug, or refactor) followed by a task number from a bug tracking software. If we need to follow a convention like this one, Git can format the commit messages for us.

Keep your commits small and focused. Work with incremental commits. And, don’t commit changes that break your project.

4. Branching and merging

What’s a Git Branch?

Using the time machine analogy, a branch is a separate timeline. Changes in a timeline don’t interfere with changes in other timelines.

Branching is one of the most awesome Git features. Git branches are lightweight and fast when compared to other VCS.

When starting a Git repository, Git creates a default branch called master. Let’s create a new branch called “testing”. For this, we will need the command branch follow by the branch name.

# Create a new branch called testing

$ git branch testing

# List all branches you have

$ git branch

# Move to the new testing branch

$ git checkout testing

# Modify the README file

# For example, add a new line

# "For example, how to create branches"

$ git status

$ git add README

$ git commit -m 'Add example to README'

Now, let’s switch back to the master branch and see what happened to our files there. To switch between branches, we need the checkout command.

# Now move back to the master branch

$ git checkout master

# See how README hasn't changed

# Modify the README file again

# For example, add "Git is so awesome, isn't it?"

$ git status

$ git add README

$ git commit -m 'Add Git awesomeness'

# See how these changes live in different timelines

$ git log --oneline --graph --all

We have created two branches, let’s see how we can combine what we have in the two branches.

How to Merge Two Branches

Merging two branches is like combining two separate timelines.

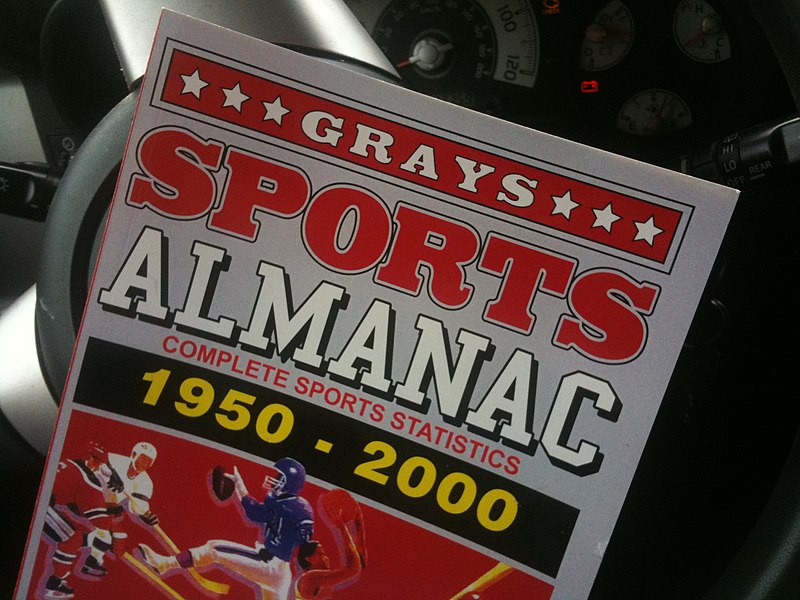

Continuing with the time travel analogy, merging is like when Marty goes to the past to get back the almanac and he is about to run into himself. Or when captain America goes back to New York in 2012 and he ends up fighting the other captain America. You got the idea!

Let’s create a new branch and merge it to master. We need the merge command.

# Move to master

$ git checkout master

# Create a new branch called hotfix and move there

$ git checkout -b hotfix

# Modify README file

# For example, add a new line

# "Create branches with Git is soooo fast!"

$ git status

$ git add README

$ git commit -m 'Add another example to README'

# Move back to master. Here master is the destination of all changes on hotfix

$ git checkout master

$ git merge hotfix

# See how changes from hotfix are now in master

# Since hotfix is merged, get rid of it

$ git branch -d hotfix

Here we have created a branch called hotfix and merged it to master. But we still have some chances on our branch testing. Let’s merge this branch to see what will happen.

$ git checkout master

$ git merge testing

# BOOM. You have a conflict

# Notice you have pending changes in README

$ git status

# Open README, notice you will find some weird characters.

#

# For example,

# <<<<<<< HEAD

# Content in master branch

# =======

# Content in testing branch

# >>>>>>> testing

#

# You have to remove these weird things

# Modify the file to include only the desired changes

$ git status

$ git add README

# Commit to signal conflicts were solved

$ git commit

# Remove testing after merge

$ git branch -d testing

If you’re coming from TFS, you noticed you need to move first to the branch you want to merge into. You merge from the destination branch, not from the source branch.

How to Move to the Previous Branch

In the same spirit of cd -, we can go to the previously visited branch using git checkout -. This last command is an alias for git checkout @{-1}. And, @{-1} refers to the last branch you were on.

# Starting from master

$ git checkout -b a-new-branch

# Do some work in a-new-branch

$ git checkout master

# Do some work in master

$ git checkout -

# Back to a-new-branch

Git master convention

By convention, the main timeline is called master. But starting from Git 2.28, when we run git init, Git looks for the configuration value init.defaultBranch to replace the “master” name. Other alternatives for “master” are main, primary, or default.

For existing repositories, we can follow this Scott Hanselman post to rename our master branch.

GitFlow Branching Model

Git encourages working with branches. Git branches are cheap and lightweight. We can create branches per task or feature.

There is a convention for branch creation, GitFlow. It suggests feature, release, and hotfix branches.

With Gitflow, we should have a develop branch where everyday work happens. Every new task starts in a separate feature branch taken from develop. Once we’re done with our task, we merge our feature branch back to develop.

5. GitHub: Getting our code to the cloud

Up until now, all our work lives on our computers. But, what if we want our project to live outside? We need a hosting solution. Among the most popular hosting solutions for Git, we can find GitHub, GitLab and Bitbucket.

It’s important to distinguish between Git and GitHub. Git != GitHub. Git is the version control system and GitHub is the hosting solution for Git projects.

No matter what hosting we choose, our code isn’t synced automatically with our server. We have to do it ourselves. Let’s see how.

How to create a repository from GitHub

To create a repository from a GitHub account, go to “Your Repositories: and click on “New”. We need a name and a description. We can create either public or private repositories with GitHub.

Then, we need to associate the GitHub endpoint with our local project. Endpoints are called remotes. Now we can upload or push your local changes to the cloud.

# Replace this url with your own

$ git remote add origin https://github.com/canro91/GitDemo.git

# push uploads the local master to a branch called master in the remote too

$ git push -u origin master

# Head to your GitHub account and refresh

6. Cheatsheet

Here you have all the commands we have used so far.

| Command | Function |

|---|---|

git init |

Create a repo in the current folder |

git clone <url> |

Clone an existing repo from url |

git status |

List pending changes |

git add <file> |

Add file to the staging area |

git commit -m '<message>' |

Create a commit with message |

git log |

List committed files in current branch |

git log --oneline --graph --all |

List committed files in all branches |

git branch <branch-name> |

Create a new branch |

git checkout <branch-name> |

Change current branch to branch-name |

git checkout -b <branch-name> |

Create a new branch and move to it |

git merge <branch-name> |

Merge branch-name into current branch |

git remote add <remote-name> <url> |

Add a new remote pointing to url |

git push -u <remote-name> <branch-name> |

Push branch-name to remote-name |

7. Conclusion

Voilà! We have learned the most frequent Git commands for everyday use. We used Git from the command line. But, most IDE’s offer Git integration through plugins or extensions. Now try to use Git from your favorite IDE.

If you want to practice these concepts, follow the repo First Contributions on GitHub to open your first Pull Request to an opensource project.

Your mission, Jim, should you decide to accept it, is to get the latest changes from your repository. After pushing, clone your project in another folder, change any file and push this change. Next, go back to your first folder, modify another file and try to push. This post will self-destruct in five seconds. Good luck, Jim.

Happy Git time!